Research & Evidence

Research Using Great Leaps

1. Shultz Ashley, Gwendolyn, The effects of Great Leaps reading on the reading fluency of elementary students with reading and behavioral deficits., (2021). Paper 3656.

This is a multiple baseline across subjects' study, using the Great Leaps for Reading Digital software with elementary students that had both behavioral and literacy deficits. An excerpt from the study can be found below.

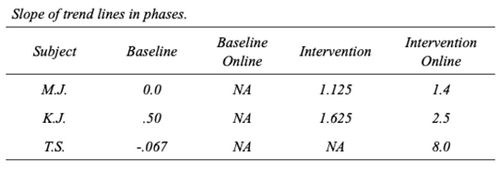

As there is one phase for two students with an N below the required eight data points (Jenkins & Quintana-Ascencio, 2020), I have chosen to compute slope for each phase by hand. In this way, visual analyzation can be supplemented by slope numbers to facilitate more accurate comparisons of the data.

The slope of the trend for each phase, for each child, with online and face to face differentiated, can be found in Table 23 below. Slope was determined by using the formula (y2-y1)/(x2-x1).

Even with the Lexile level increasing frequently, each child did have an increase in reading level. Table 23 shows that each child did have an increase in rate and slope of their trend during the intervention stage. The slope of the trend line for each child increased in intervention, although much greater for M.J. and T.S. than K.J. The mean words per minute increased from baseline to intervention as well. This does show a replicated effect, although not a functional relation.

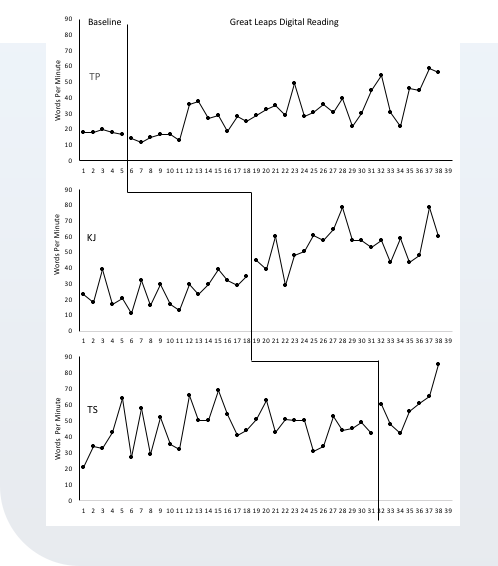

The Great Leaps graph, Figure 7, shows that although the level of the reading passage increased every few sessions, as students made “leaps”, progress was continual. Visual analyzation of the Great Leaps graph, Figure 7 shows the progress of each individual student. M.J. had slow, steady, upward progress. K.J. had progress that was quicker and steeper than that of M.J., while T.S. had rapid, steep progress through the levels. When visually interpreting the graphs of both the Great Leaps words per minute and the quick read words per minute, it is important to note the similarities and differences.

M.J. had data that was wildly divergent in the beginning of the intervention, then scores began to follow a similar pattern as the intervention progressed. K.J. had intervention graphs that followed the same peaks and valleys between the two data sets. Although the numbers are not the same, the acceleration and deceleration are nearly the same each day. T.S. did not have these similarities in data sets. His data sets show nearly an inverse relationship at several points during intervention (Shultz-Ashley, 2021)

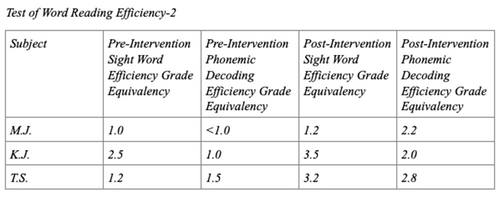

Yet another piece of evidence shows that this intervention, although facing the challenge of multiple modalities, was indeed effective for these students at this time. In order to verify reading levels and ensure that the subjects were two or more grade levels behind, a Test of Word Reading Efficiency-2 (TOWRE-2) assessment was conducted with every participant. In the table below, the gains of each student are evident.

The data shows that these students had significant gains with the use of Great Leaps, which only lasted six weeks. Students continued to use the program beyond the length of the study for their benefit.

2. Cecil D. Mercer, Kenneth U. Campbell, M. David Miller, Kenneth D. Mercer & Holly B. Lane (2000) Effects of a Reading Fluency Intervention for Middle Schoolers With Specific Learning Disabilities, Learning Disabilities Research & Practice15:4, 179-189.

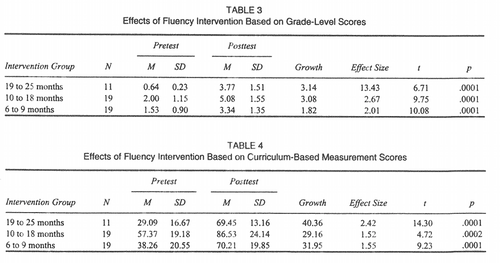

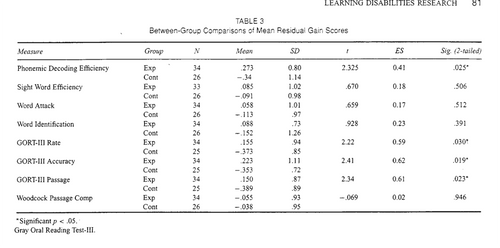

49 middle school students diagnosed with specific learning disabilities were administered the Great Leaps reading program in three groups set by differing intervention duration, with the first group averaging 24 months, the second group averaging 15.5 months, and the third group averaging 7.2 months of intervention. The intervention was implemented up to 5 days a week subject to availability by a certified special education teacher in year 1, and a trained teacher assistant in years 2 and 3.

Curriculum based assessments were used in the pretest and posttest to determine grade level growth (Table 4), along with grade-level scores in the Great Leaps passages themselves (Table 3). These assessments were comprised of 200+ word reading passages graded on the Macmillan Series R. Fry's Readability Formula, where the student's highest grade-level passage successfully read in one minute with 10% or fewer errors would have its correct words per minute recorded as the fluency score in Table 4.

3. Spencer, S. A., & Manis, F. R. (2010). The effects of a fluency intervention program on the fluency and comprehension outcomes of middle-school students with severe reading deficits.Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 25(2), 76–86.

Seeing promise in the previous Mercer et al. study, Spencer et al. chose to investigate Great Leaps with a randomized controlled design and standardized measures of fluency and reading comprehension. Taking place at two middle schools, the researchers finished the study with a total of 60 students selected from Special Day Programs which represented the most profoundly reading-delayed population at the two schools.

Paraprofessionals were to work the Great Leaps program 4 days a week though average sessions per week varied from 2.1 to 4.1 with a combined average of 2.7 sessions per week and 53.2 sessions total. The control group received 10 minutes of instruction from paraprofessionals using the Skills for School Success program, working on general classroom and study skills.

“Given that the posttest fluency scores are based on more difficult reading material, the fluency scores are outstanding.” The 1.82 year grade level improvement found in 6 to 9 months' intervention in learning disabled students corroborates what is typically found with Great Leaps use nationwide.

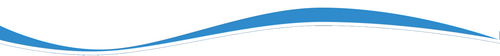

Results of Experimental and Control Group Comparisons:

“Residualized gain scores (RGS) were used to calculate differences between the experimental and control group outcomes. RGS were chosen in order to mediate the effects of regression toward the mean that may occur when comparing raw change scores.

RGS were calculated by using regression analysis to predict posttest scores from the correlation of the pre- and posttest outcomes, then subtracting the predicted scores from the actual posttest scores (De Vaus, 2001). Mean RGS for each group were then compared through the use of independent t tests.

Outcomes on Fluency and Decoding Measures:

“Means of the RGS for the experimental and control groups are reported in Table 3. The experimental group made significantly more progress than the control group on the Phonemic Decoding Efficiency assessment (p = .025), with an effect size of 0.41 (Test of Word Reading Efficiency [TOWRE]; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999b). The experimental group also made statistically significant gains in mean RGS for GORT-III Rate (ES = 0.59), GORT-III Accuracy (ES = 0.62), and GORT-III Passage (ES = 0.61) when compared to the control group. According to Cohen (1988), effect sizes of .20 or less are considered small, .60 is considered moderate, and .80 and above is considered large. From the Discussion, “The results of the group comparisons of the reading data clearly indicate that the intervention was successful in improving reading fluency. Students in the experimental group made significantly more progress in fluency than the control group as measured by their performance on four measures:

(a) TOWRE Phonemic Decoding Efficiency, (b) GORT-III Rate, (c) GORT-III Accuracy, and (d) GORT-III Passage. In addition, these outcomes reveal that the students were able to generalize their fluency gains to novel material. The reasons for this success are likely related to the design of the Great Leaps Reading program (Campbell, 2005), which closely aligns with the recommendations of the majority of the literature on effective fluency instruction:

(a) clear performance criteria for the students, (b) systematic progression into harder material as students master each level, (c) implementation by adults, and (d) incorporation of regular error correction and feedback. These components were recommended by Chard et al. (2002), Therrien (2004), and the NRP (2000) in their meta-analyses of fluency research.”